When a school celebrates one hundred years, it is not merely an anniversary. It is a cultural landmark. Bishop’s High School, Tobago, founded in 1925, reached its centennial this year, and among its commemorations was one of the most striking tributes to its legacy: the 100 Years of Creativity Art and Literature Exhibition. Held from September 5 to 21, 2025, at the Shaw Park Complex, the exhibition was a living archive of talent, resilience, and imagination, showcasing how generations of Bishopians and Tobagonians have engaged with art and literature to tell their stories and shape their society.

For two weeks, the exhibition hall transformed into a vibrant confluence of colour, texture, and narrative. Visitors wandered through galleries that juxtaposed historic publications with bold contemporary artworks, each piece carrying echoes of the past and whispers of the future. The exhibition was not only about art for art’s sake. It was about reclaiming heritage, affirming identity, and celebrating a century of educational and cultural stewardship.

An Exhibition Rooted in Legacy

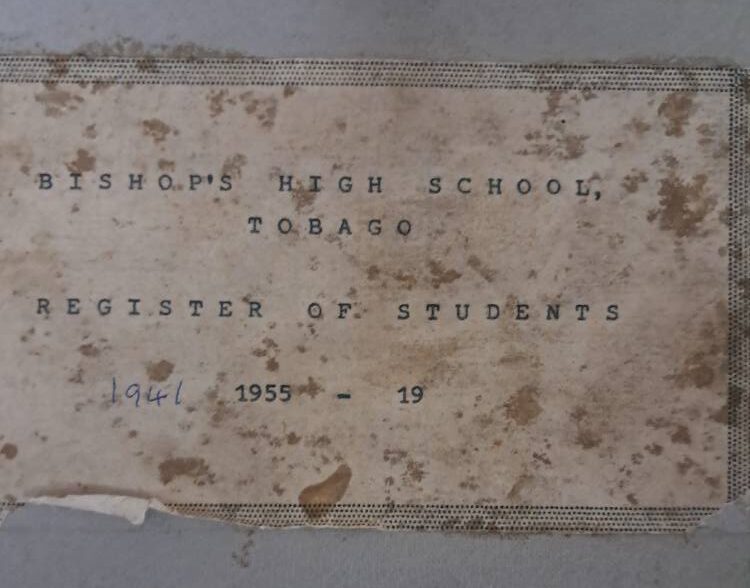

The Bishop’s Centennial Committee designed the event as a tribute to creativity across generations. On one wall, archival pieces and historic publications reminded viewers of the school’s intellectual foundation. The Ansteian, Bishop’s High School’s annual magazine first published in the early 1960s, stood proudly beside works like The Story of Tobago (1973) by C.R. Ottley and From Mason Hall to White Hall (2016) by alumnus and Prime Minister Keith Rowley.

These texts reminded visitors that the school has long been a crucible for leadership and scholarship, producing voices that contributed not only to Tobago’s narrative but also to the Caribbean’s collective history.

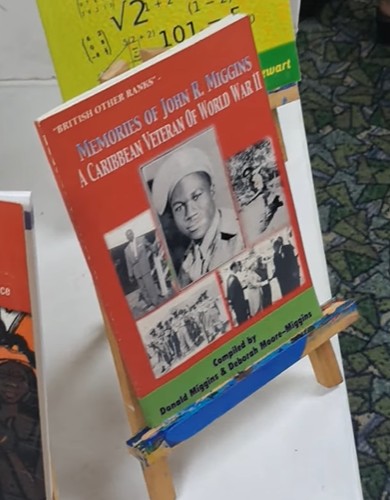

The exhibition was far from nostalgic alone. Alongside these historical treasures stood contemporary titles such as John Arnold’s Tobago Son (2023), Deborah Moore-Miggins’ Laugh Not…Live Not (2022), and the newly published History Matters (2025) by Heather Cateau, Rita Pemberton, and Ronald Noel.

These works served as both mirrors and windows: mirrors of the lived Caribbean experience and windows into the questions shaping the region today.

A Gallery of Imagination

If the books grounded the exhibition in words, the artworks gave it wings. Bold, expressive canvases captured Tobago’s natural beauty, folklore, and social fabric. Sarah Jude’s Engulfed by Nature (2025) enveloped viewers in sweeping greens and blues, a visual meditation on humanity’s relationship with the environment. Akilah Thomas’s Unity in Diversity (2024) translated Tobago’s multicultural ethos into a striking interplay of color and form. Caelyn Baynes’ Courland Monument (2024) and Fort King George (2024) offered historical reflection through architectural landscapes, reminding audiences of Tobago’s layered colonial past

The gallery also invited playfulness and imagination. Terrance Murray’s Wonderland Tea Party (2020) and Magical Scholar (2020) brought whimsical, almost surreal elements to the exhibition, contrasting with the quiet dignity of Chelsea Mills’ Pride (2016) or the folkloric resonance of Joyanna Duncan’s Papa Bois at Peace (2024). Collectively, these works revealed how Tobago’s artists negotiate between tradition and innovation, rooting their art in heritage while experimenting with modern visual languages.

Artworks and Literature for Sale

What set the exhibition apart from many centennial showcases was its accessibility. These were not merely items to admire behind glass but works available for purchase. Paintings, prints, poetry, and prose were ready to enter homes and personal collections. By placing art and literature on sale, the exhibition blurred the line between observer and participant. Patrons became custodians of culture, carrying pieces of Bishop’s centennial legacy into their daily lives. For emerging artists and writers, it provided not just visibility but tangible support, affirming that creativity has economic as well as cultural value.

A Gathering of Generations

Perhaps the most moving aspect of the exhibition was its atmosphere. Alumni who once walked the halls of Bishop’s High mingled with students just beginning their journeys. Parents brought children to encounter Tobago’s creativity firsthand. Tourists found themselves immersed in the island’s cultural depth beyond beaches and festivals.

One alumna, pausing before a painting, remarked, “This exhibition feels like a homecoming of the spirit. We see ourselves here, not only who we were, but who we are becoming.” That sentiment rippled throughout the venue. This was not simply an art show, but a collective act of remembering and reimagining.

For current students, the exhibition was an affirmation that their creative pursuits, whether painting, writing, or otherwise, are part of a legacy stretching back a hundred years. For elders, it was an opportunity to see their efforts honoured, contextualized, and carried forward.

Leadership Behind the Scenes

Behind this landmark event was a dedicated organizing team that brought vision, discipline, and heart to the project. The exhibition was spearheaded by Nazim Baksh, who served as Team Lead and chief organizer, ensuring that the centennial’s artistic voice was both authentic and inclusive. Supporting him was a committed committee whose talents spanned logistics, curatorial insight, and community engagement. Members included Cindy Ramnarine, Ronette Ried Guillard, Shonari Richardson, Johnathan Cravelle, Bryan Jordan, and Dr. James Armstrong. Their collective effort ensured that the exhibition was not simply a display but a carefully curated experience that balanced heritage with innovation, reverence with celebration.

The committee’s work also reflected the wider Bishopian ethos: collaboration across disciplines, service to community, and a belief in the transformative power of education and creativity.

Cultural and Educational Impact

The significance of the Art and Literature Exhibition extended beyond Bishop’s High School. Tobago has long wrestled with questions of cultural preservation, representation, and visibility. Events like this demonstrate how art and literature serve as powerful tools for education and empowerment. By highlighting both local talent and scholarly contributions, the exhibition reinforced the message that culture is not peripheral to progress but central to it.

For the broader Tobago community, the exhibition showcased the island not merely as a tourist destination but as a cultural powerhouse. For educators, it underscored the value of integrating creativity into pedagogy. And for the artists and writers themselves, it validated their role as chroniclers of history and shapers of the future.

A Centennial Beyond Celebration

Bishop’s High School’s centennial celebrations have included concerts, sporting events, and acts of service, but the Art and Literature Exhibition stands out as uniquely fitting. Education is not only about examinations and degrees. It is about cultivating imagination, critical thinking, and expression. By foregrounding art and literature, the exhibition highlighted those softer yet profound legacies of the school.

It also hinted at what the next century might hold. If the past hundred years have produced such a wealth of artistic and intellectual contributions, what might the next hundred yield, especially with new generations drawing inspiration from both tradition and innovation?

Closing Reflections

When the exhibition closed its doors on September 21, it left behind more than empty walls. It left memories of conversations sparked, books purchased, and artworks admired. It left the sense of a community connected across generations by creativity. Most of all, it left an enduring reminder that the centennial was not just about looking back. It was about looking forward with the assurance that Bishop’s High School’s spirit of imagination and expression will continue to thrive.

In celebrating a century through art and literature, Bishop’s High School reminded Tobago and the wider Caribbean that creativity is the heartbeat of identity. It is in the brushstroke of a painting, the cadence of a poem, the turn of a phrase in a novel. And as long as these voices and visions endure, the legacy of Bishop’s High will remain not only in history books but in the living, breathing culture of its people.